Things you’ll learn from this post

- Sulphur is not evil and the levels added to wine are quite low compared to a lot of other food products we commonly consume.

- It’s used to stop a wine oxidising and for microbial stability (to stop bacteria and yeast growth).

- A wine bottled with less sulphur will mature faster than the same wine bottled with more sulphur.

- Knowing the winemaker’s approach to sulphur use will allow you to cellar a wine with confidence – doesn’t override tasting it!

- 2 x Pro-Tips at the end of the article.

What is Sulphur?

Sulphur in its elemental form is a yellow crystalline substance and is found in this form in certain areas of the world, such as Sicily. When it is burned it forms sulphur dioxide, which is an acrid gas. In high concentrations in the atmosphere it is dangerous, particularly to people with breathing conditions. However, in small concentrations, it has the beneficial effect of killing micro-organisms, including bacteria and yeast which left unchecked would spoil wine. In this article I explore the use of sulphur dioxide in winemaking and for convenience will refer to it as sulphur, which is the usual shorthand nomenclature used by winemakers.

The Story So Far

In the late 1990’s a lot was happening in the wine industry. Trends had seen reduced additions of sulphur to both white and red wines. There were a couple of preservative-free wines on the market from the big producers. In spectacular style, without a match between production levels and shelf life, the wine went off before it could all be sold.

The incidence of Brettanomyces in reds was very high. Chardonnay as a whole was still being picked very ripe and it was common to see oxidised wines in cellar doors.

Around the same time, on the other side of the planet, Premature Oxidation, or, Prem-Ox, was rife in White Burgundy. Prem-Ox was attributed to an array of factors, bottling techniques, corks, changes to some winemaking practices, and, lastly reduced sulphur additions pre-bottling.

Before you make sulphur some kind of Boogie Man, you’ve got to put the amount of sulphur added to wine into perspective. Firstly it’s naturally present in wine. Secondly, it is only added at low levels. There’s usually a little more in white wine than red wine. Sulphur is added to dry table wines at roughly 3-5% of the level of additions made to products like dried fruit and french fries. Prepared soups and packaged meat hit levels heading toward twice that of wine!

You also need to know five things:

- The higher the quality of wine the less sulphur is needed in making the wine.

- The lower the pH the more effective sulphur is at doing its job. Less will need to be added to protect the wine. The more acid there is in a wine the lower the pH will be.

- How you make the wine can impact how much oxygen will affect it as it ages. Making it in the right way can give it a higher level of stability against future oxidation.

- Wines have differing capacities to handle exposure to oxygen.

- A certain base level of sulphur provides a wine with microbial stability.

Back in Australia, we were installing a bottling line at Yering Station, establishing quality controls. We’d shifted to a fresher style of Chardonnay, picked earlier, with greater natural acidity had commenced. The talk was around sulphur levels at bottling. Historically we’d bottled with a free (active) sulphur of 25ppm.

With the bottling line going in we were acutely aware of the impact of oxygen, just 1ppm of dissolved oxygen would consume 4ppm of sulphur. At just 25ppm free sulphur it wouldn’t take much oxygen and then, at the time, oxidation associated with cork variation, to result in oxidation of the wine and potentially considerable variability bottle to bottle.

The decision was made to add an extra 10ppm sulphur bringing the free sulphur up to 35ppm and giving us a buffer to cover off many of the potential sources of oxidation at and after the point of bottling.

This is not because we were afraid of oxidation or oxygen, we’d already carefully raised the wines from the point the grapes were picked through the maturation process which slowly developed the wine, in part through oxygen contact, and, it needed no further oxygen interaction at the point of bottling. It was ready!

Here’s the rub, the higher the free sulphur levels the longer it would take for the wine to be ready for consumption. At 35ppm free sulphur, there’s not much of a wait to be had, the wine just needs a few months to settle after being shaken up on the way to the bottle.

You can read about my winemaking experience at Yering Station in the Wine Bite Mag, covering 3 vintages.

The Experiment

The experiment was to bottle magnums of the wine, one set with the standard sulphur addition and the other with an extra 50ppm.

The image below shows the two wines. Exactly the same wine. Two magnums, bottled in exactly the same way, under the same closure, cork in this case. The only difference is the glass on the right had an extra 50ppm, or, mg/l added to the magnum.

The Wine:

Yering Station Reserve Chardonnay 1999 – A cracking Chardonnay year in the valley.

When we ran the experiment we added an extra 50ppm to a magnum, still low quantities compared with other foods, we’d need to wait for some time. You can easily smell the sulphur in a wine with this level of sulphur addition at the point of bottling.

In 2009 wines from the standard bottling were tasted alongside 1er Cru Burgundies at an event held at Francois to critical acclaim.

Now 10 years later we compare the two magnums.

So what’s the difference?

Appearance:

You can clearly see the glass on the left has a dark golden colour, while the glass on the right still has a youthful appearance. Yes, the glass on the right is the one with the extra sulphur added to it.

Aroma:

If I was given these wines blind I would have said the wine on the right was 10 years younger, the fruit was still vibrant, fresh, yet a significant integration and seamless scent from a slow maturation had developed. The glass on the left was quite toasty, nutty, honeyed and had a hint of aldehyde, commonly described as bruised apple.

Flavour:

The vibrant fruit and seamless aromas carried through to the palate for the wine with the extra sulphur. The wine on the left had some lovely developed characters, the fruit falling away a little and an edge of hardness from the low level of aldehyde coming through.

In summary, the wine with the extra sulphur addition had been protected from oxidation in the bottle through near 20 years of maturation. The wine without the extra addition had easily made it through 10 years, but, today whilst fun to drink wasn’t at its peak.

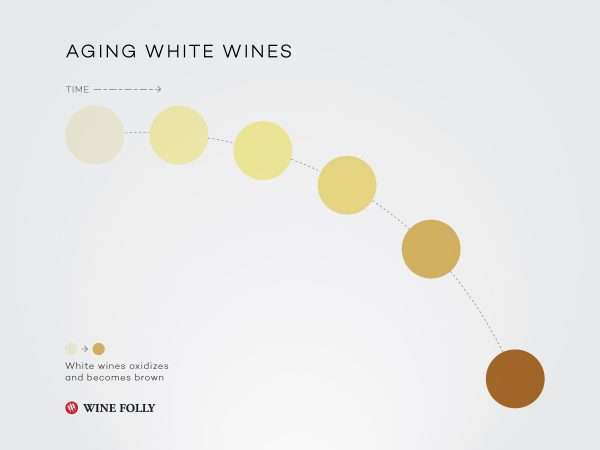

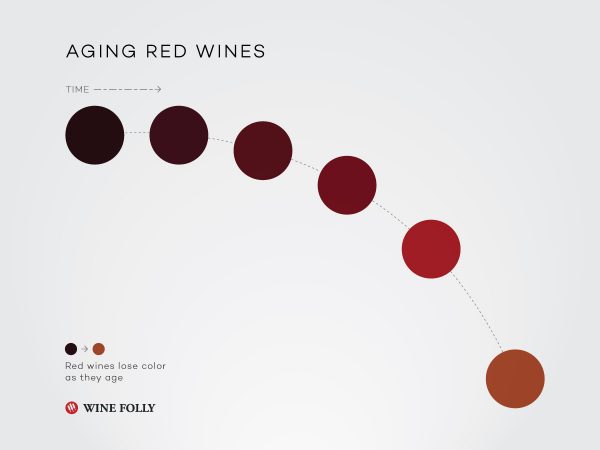

The progression of wine colour with age

White wine will get dark with age as small chemical compounds called phenols oxidise and turn brown, these are the same chemicals that cause apples and pears to go brown after they’ve been cut. As they are small they tend to remain mixed into the wine too.

Red wines tend to get lighter as they age, the colour compounds, anthocyanins, are much larger than the phenols in whites. They tend to form long chains with other tannins, this can stabilise colour, while they remain in solutions, but, give it less intensity. If they become so big that they fall out of solution the colour intensity of the wine will reduce.

Pro Tips

Pro-Tip 1: Looking at old bottles before buying

Looking through a bottle at its colour will give you an idea of how it’s holding up. If there are multiple bottles of the same aged wine look through a few and find the wine with the brightest colour. For whites, less colour, not brown and for reds, darker brighter colour, not brown either. Over time you’ll get an idea of what is definitely gone and potentially avoid a dud purchase. You can see the dramatic difference in colour of the Chardonnay experiment. Same wines, same bottle, the one on the right has the extra 50ppm sulphur in it and has not oxidised after 20 years.

You can do the same when you’re looking at wines from your cellar.

Pro-Tip 2:

You can freshen a bottle of old wine by adding a tiny amount of sulphur to it and letting it rest for 48 hours before drinking it. Check out the article: “Wanna know how to save a 49 year old wine … READ THIS!”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.