Prologue

We are fortunate to have in our midst an expert on Spanish wine, Scott Wasley of The Spanish Acquisition. I’m slowly working my way around Spain, in a large part through glasses shared with Scott. When he called to invite me to a tasting of Rioja dating back to 1955 I felt both honoured and excited at the prospect. When bottles like these are on song they are rare gems!

In Scott’s article below he explores the region of Rioja, a little of its history, the classification system and the challenges of politics in driving the quality of the region forward.

Many of us were first exposed to Rioja in the form of excessively ripe, over-oaked, oxidised cumbersome wine. Politics & corruption taking a region capable of offering creations of beauty that ought not exist and offering up an ocean of swill.

Like all wine regions of the world, there have been those who have railed against this abuse and sought to be the exception.

The wines of these anarchists are the stuff of legend. Historically many aged their Rioja for 6-10 years in barrel prior to a further 8-10 years in bottle before release. Some still do today although the trend has shifted to much shorter ageing.

Rioja’s reds blends are dominated by Tempranillo with portions of Garnacha, Graciano & Mazuelo (AKA Carignan or Careñina) and in some wines small portions of white varieties. Each of these varieties plays its part in adding plush fruits, tannins and the acidity needed to age for extended periods.

The best have perfumes that ought not exist with incredible complexity harmony, fine tannins to grace your tongue and can live forever!

Rioja beyond Reservas and Co

by Scott Wasley, The Spanish Acquisition

There’s no such thing as Rioja Alta, Alavesa and Baja

or: how I stopped listening to the Consejo Regulador and learned to understand Rioja

“We’ll be drunk on Sunday, and again on Tuesday, so we cannot have you for a visit on Monday …”

This exquisite wisdom came from the offices of the Consejo Regulador of DOCa Rioja, in response to my request for an appointment at their offices on a (non-public-holiday) Monday in between two wine festival party days. No matter that I import eight of Rioja’s finest producers into Australia. Nor that I had with me four Aussie-sommelier-types, spending a week in-depth learning the region. Nor even that I was researching the Rioja portion of a forthcoming book on Spanish wine.

There’s a party on … we can’t see you.

Now, it would be merely bitchy of me to relay this story, were there not a deeper point to be made. This article argues that the ‘official’ Rioja promulgated by the offices of the regulatory body is far from the only way to view this extraordinarily picturesque wine region. In fact, that there is nothing really to see in the official view – its explicit purpose is to occlude, dumb down and homogenise.

A desire for improved quality is no part of the picture.

So, what is this conventional view?

It consists of three equally unsatisfactory aspects:

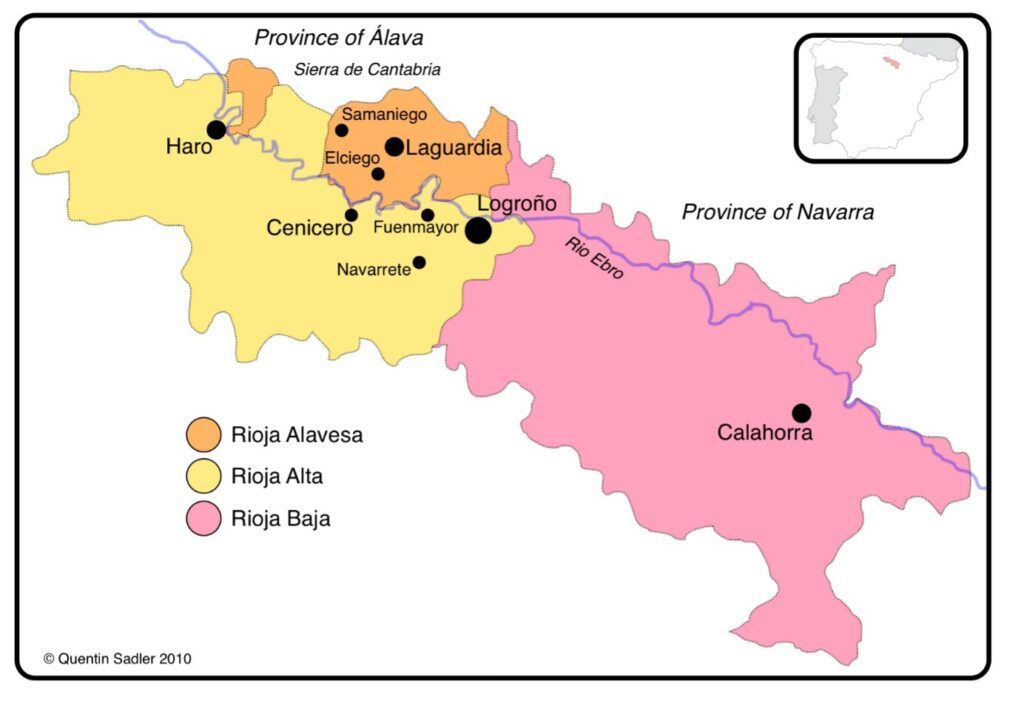

· that Rioja can and should be understood as three geographical parts: Alta, Alavesa and Baja

· that village-specificity has no place in understanding (or promoting quality in) Rioja wines

· that Rioja is best known through the ageing categories of Crianza, Reserva, Gran Reserva.

“there’s no such thing as Rioja – there are many Riojas”

Seen as currently promoted, Rioja is “like going to Burgundy and only finding generic AC Burgundy”, without the highs and lows, nuances and sense of place afforded by a sub-regionalised view of villages, vineyards and crus … where geographical reality takes precedence (over the actions of any grower or producer, or temporal influences like seasons and trends) in understanding the wines of a place. The above quotes are from quality Rioja growers. These guys want to identify their Riojas according to the village location in which the fruit is grown, but, here’s the thing:

In Rioja, the village is illegal.

Village-and-vineyard nuances in Rioja are supressed by the Consejo Regulador. The result is a Rioja unified as a broad ‘brand’ akin to ‘Wine of South-East Australia’ (as industrial exports from ‘Down Under’ are known). ‘Brand Rioja’ is promoted at the behest of the giant industrial companies who pay the Consejo Regulador on a kilo-by-kilo basis. And, there are many, many kilos in Rioja Generico.

So, the first issue is to exemplify the lack of village (and vineyard) specificity allowed in contemporary Rioja. Further, to note that this is a truly recent development: I have Rioja in my cellar from as recently as 1981 where the village of origin was named loud and proud in label font larger than that proclaiming the producer. So, the great (and terribly sad) irony of contemporary ‘official’ Rioja is this: while Spain’s other regions (Bierzo, Priorat, Ribeiro and so on) awoke post-fascism during the 1980s and proceeded to re-discover and recover their heritage – the old ways, places and historical varieties specific to their locale, DOCa Rioja has increasingly deferred to generic and industrial precepts.

It cannot be over-stated how deliberate this retreat has been. While DOCa Rioja sticks its head in the sand (the better to see), DOQ Priorat, for example, has initiated a sub-regional geo-regulatory order of village locations, then place names and then specific vineyards. None of this has recently been made up, it has always been there. Priorat is now mapped, named and recognised according to a deeply historical sense of place. DO Bierzo is currently working on following suit. So too could it be in La Rioja. When they come back from lunch, perhaps …

But, to lament the absence of the village as an organising logic of identity in La Rioja is to get way ahead of ourselves. Surely we can’t understand a village (likewise, of course, the vineyard) if we don’t know where it fits into the place? The first fault and the greatest limitation to comprehending Rioja (at least from a quality standpoint) is to view Rioja as divided into portions known as Rioja Alta, Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Baja. This division is nonsense from the standpoint underpinning our argument here: the nexus between terroir and wine character/quality.

Ladies and Gentlemen, introducing ‘Rioja Superior’

My overarching point is thus stated:

It’s possible to view this surpassingly beautiful wine region in exactly the same way as one views Burgundy or Barolo: as a cohesive geographical region, further defined by a preferred soil type highly advantageous to the production of quality and great wines. This optimal dirt is then more deeply understood on a villages-and-vineyards basis. Take Burgundy, for example: no matter how patchy the vinous offerings of the region, it’s geographical makeup is clear, and we enter into consideration of each and every bottle of Burgundy via its place-name (excepting generic AC Burgundies). As we drive south to north through the Cote D’Or, along the A31 between Lyon and Dijon, our car tracks are in the valley floor on soils suited to cash crops, towns and industry. As we look left out of our window we gaze up to a series of limestone-clay hillslopes and mark off the known-and-named places as we pass: from Santenay, through the villages of the Côte-de-Beaune to Beaune itself and beyond through the ‘made-guy’ villages of the Côte-de-Nuits, from Nuits-St-George up through Gevrey-Chambertin, then out past Fixin and north towards Chablis.

The useful view of La Rioja is the same:

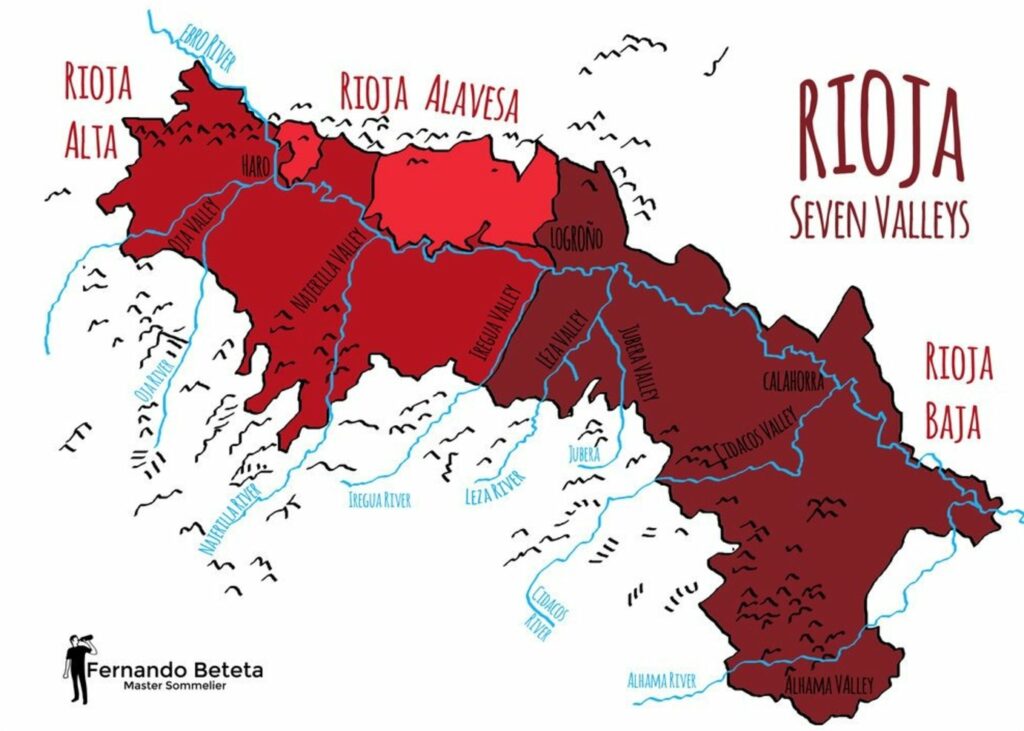

Commencing near Haro, if we drive from west to east towards Logroño, we’ll discover ‘Rioja Superior’ (by way of temporary appellation). Driving along the main highway, the AP-68, our tyres track through the fertile flood plain soils below the Rio Ebro, as the river flows to its Mediterranean delta away to the south-east, below Priorat. Above us, looking left out of the car window, the north shore of the Ebro stretches west to east under the high Sierras of the Cantabrian mountains. Between the river and the mountains, Rioja Superior is an easily drawn continuity of limestone-clay hill-slopes. Here are a procession of small wine villages nestled in the intermediary hills. From outliers such as Fonzaleche and Cuzcurrita del Rio Tiron, we pass Haro, then travel through Briñas, Labastida, San Vicente, Laguardia, Lanciego and Laserna (among others) before arriving in Logroño.

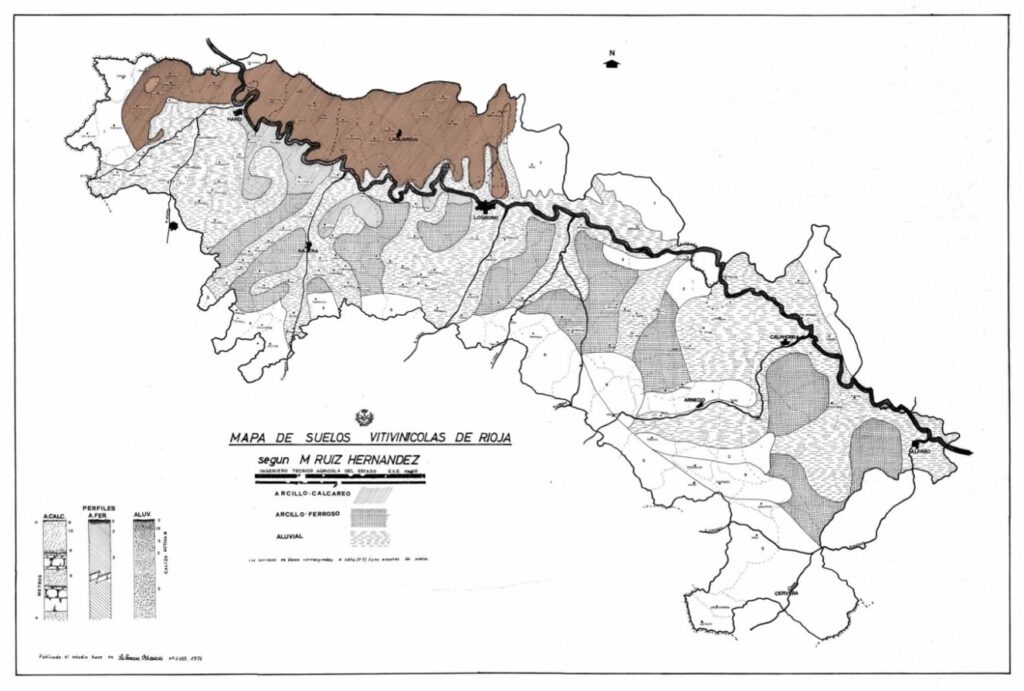

Rioja Superior, looking north as we drive west to east, fits almost perfectly between Haro and Logroño, between the river and the mountains. A geographically neat terroir defined by arcillo-calcareo (clay-limestone) soils. Outside this core of low nutrient, cold hill-soils, the vast majority of land appellated as Rioja grows low-quality Rioja Generico (along with some of the world’s finest fruits and vegetables) in highly fertile soils. Diving the region into Rioja and Rioja Superior allows us to discriminate the potential for fine wines in the cold soils above the river from the overly fertile ferrous and alluvial soils of the flood plains below it. Rioja Superior is just one-tenth of the land area producing DOCa Rioja wine.

The division of Rioja into Alta, Alavesa and Baja takes no account of the relationship between soil and wine-growing quality. Note that not even 10% of the land mass sanctioned as Rioja Alta (and only a bit better than half of Alavesa) is on the soil profile best suited to quality red wine production. Alta and Alavesa are mere political distinctions between Castilian (Spanish) and Basque Rioja. The patch I am calling Rioja Superior is a remarkably cohesive terroir, within which it is incredibly easy to then drill down into a village by village view of the place. From here, if we wish, it is simple to compare the essentials of this village versus that … and then to go on about vineyards or crus. The Alta/Alavesa/Baja model is useless, as it fails to focus on the dirt that makes the best wine.

Note that the soil map of La Rioja which underpins our argument was published in 1974

“You could see who was coming to kill you”

Let’s take an example. In the far north of Rioja Superior lies a significant estate – La Granja de Nuestra Senora de Remelluri. Remelluri lies directly under the peaks of the Cantabrian Sierras, high up on slopes with panoptical views of all Rioja below to the south. Since the 12th century, this was a place where the villagers would gather to observe, and should an oncoming invasion be spotted, they would scramble up into the high hills and disappear in the mountains. Over time, Remelluri became an agricultural estate and eventually La Rioja’s first discrete wine estate, whereby the wines of the estate were grown, made and bottled on the estate (with the help of some local growers). A producer of particularly lovely Rioja, Remelluri is also famous as the estate on which the young Telmo Rodriguez grew up, and where as young winemakers, Telmo and his long term winemaking partner, Pablo Eguzkiza, made their start.

And now, they are back. Telmo and his sister Amaya have run Remelluri on behalf of their family since the retirement of their father, Jaime Rodriguez, in 2009. The first decisive measure of the new regime was to purge Remelluri’s wines of the non-estate fruit which had crept into production over the years. Since ’09, all Remelluri wines are entirely of the estate, which is now committed to full biodynamic and organic farming. Sensitive to the well-being of the local villagers, however, Remelluri did not simply cancel the existing contracts to buy fruit from growers. Instead, they decided to make a separate wine from this bought in fruit, from and for the growers, and now sell it on their behalf as a separate brand: ‘Lindes de Remelluri’ … wine from the sides of Remelluri.

The grower wine is in fact a pair of wines, and are organised (you guessed it …) by village. The Remelluri estate lies in between the villages of Labastida and San Vincente de Sonsierra. Labastida is encountered soon after leaving Haro travelling north-east into the ‘top’ of Rioja. After Labastida and past the turn-off to Remelluri, we reach San Vicente then head south-east towards Logroño. The growers from the western side of Remelluri are gathered in a wine called ‘Lindes de Remelluri – Viñedos de Labastida’ while fruit from the growers on the eastern side becomes a second wine, ‘Lindes de Remelluri – Viñedos de San Vicente’.

When you taste the two grower wines side-by-side, the variance according to village location is quite remarkable. The Labastida wine is spare and elegant with fine, herbal tannin, smelling and tasting of Spring. The San Vicente wine is demonstrably blockier, built on sturdy ‘four-square’ tannins, considerably denser and more earthily fruited. Both are unmistakeably ‘Rioja’, and delicious expressions of quality fruit. Identically handled, without any affective winemaking influence, they are startlingly expressive of village-location differences. Labastida and San Vicente are just 5km apart along a little A-road winding through the hilly north of Rioja.

on taking a drive through La Rioja …

As mentioned at the outset, there is the AP-68 freeway below the river, which roughly separates the hilly limestone-clays of the Ebro’s north shore from the alluvial clay floodplain to the south, and whisks one from Haro to Logroño un-interrupted by little wine towns. The A-124 (just mentioned above), winding its way through the hills of the north constitutes a second path between Haro and Logroño, and takes one through Briñas, Labastida, San Vicente de la Sonsierra, Samaniego, Laguardia and past La Serna and Lanciego. Between these two ways is the N-232 which winds along the Ebro (largely paralleling the freeway) and takes us from Haro through Briones, Torremontalbo, Cenicero and Fuenmayor on its way into Logroño. Unless in a hurry, one would rarely use the freeway, rather the high road (A-124) or the low (N-232). Between these, a series of minor A-roads connect other villages such as Baños de Ebro, Cenicero, Navarette and Elciego.

Winding your way along these little country roads, you experience La Rioja as a magical place. Majestic mountains loom over pretty medieval villages dotted throughout rolling hills patch-worked with vineyards, alive with wildflowers and demarcated by dry-stone-wall fences maintained by hand for centuries. If you stand breathing the pure, cold mountain air in the central-northern town of Laguardia, for example, the sense of history, as well as the utter beauty of the place is manifest. Laguardia is set atop a lofty hill, which allows the gaze to travel Rioja in all directions: high up and immediately in back the Cantabrias block the Basque coast to the north; 40km south, below the Ebro, a second range – the Sierra Demanda – marks La Rioja’s southern border. In between, vineyard-laden hills rise from fertile valleys whose rivers run inevitably into the Ebro, and ultimately the Mediterranean.

Laguardia is a medieval town whose fortress outer wall has remained virtually unchanged since the 13th century. These battlement walls contain ‘two villages’: that which you see built above-ground, and the second, a hidden community of interconnected cellars dug by hand into the sandstone-limestone bedrock. In the past, when marauders came and defeat meant retreat, the villagers would disappear into a maze of underground granaries and cellars.

But really, why take this nostalgic detour to Laguardia?

Laguardia – frontier town

Because, here, smack bang in the middle of Rioja Superior, one of Rioja’s finest producers has withdrawn its name from the appellation entirely … Bodegas y Viñedos Artadi has just taken its name off the Rioja program, citing DOCa Rioja’s general lack of ambition regarding wine quality, and the bureaucracy’s policy of blocking real geographical identification of the region’s wines. Artadi is based from the outset on two principles: organic viticulture and site-specific wines from the village of Laguardia. But, from the 2014 vintage, Artadi’s lovingly nurtured local wines will no longer be released as Riojas – they will simply be Spanish country wines from the Alava (Basque) village of Laguardia.

Such acts of defiance, where quality producers are so damning of the lack of ambition and related quality strictures promoted by wine bureaucracies that they withdraw from their appellation, are not unheard of in the wine world. Raventos i Blanc in the Penedes town of Sant Sadurni d’Anoia have recently withdrawn from DO Cava and have set up their own quality sparkling wine appellation: Conca del Riu d’Anoia – population, one producer. Anselmi’s scorn of the Soave appellation is another that comes to mind. In all such instances the courage of commitment on display is deeply admirable. However, it would be preferable for stars such as Artadi to stay within a strengthened and confident administration which was robustly focused on matters of quality as much as quantity.

A ‘frontier’ moment has coalesced in Laguardia right now. This political disaster offers the chance to focus and summarise matters – to consider what we mean when we talk about ‘Rioja’. Artadi clearly feel that DOCa Rioja is not talking about ‘Rioja’ in any way relevant to the geographical reality and quality aims of Artadi’s wines.

So, what DO we mean when we talk about ‘Rioja’

The ‘official’ version of ‘what is Rioja?’ is at best a partial explanation. In fact, many of the best wines of Rioja, and many wines which could argue strongly that they have great typicity, simply do not fit. That which does fit the commonplace view has just two parts: firstly, Rioja as ‘Reserva-etcetera’ are wines defined by how long they are barrique-and-bottle aged in the bodega; and secondly, the Alta-Alavesa-Baja version of geographics, which tells us nothing about the soil in which it was grown. The only geographical information in the model is utterly empty of meaning. In DOCa Rioja, quality is determined exclusively on behalf of wines aged in 225 litre barriques. These are often early picked, racked and handled heavily in the attempt to make ‘Spanish Claret’. Rioja has no language for wines other than ‘Reservas and co’, which is not to suggest that these wines are invalid, ahistorical or anything else … just that they are only a partial telling of Rioja’s possibilities.

There is a historical connection between Bordeaux and Rioja, dating to the late 1800s. The portal known as Barrio de l’Estacion (the ‘train station suburb’) connected Haro to Bordeaux by train, allowing the French to come to La Rioja after their vineyards were wiped out by phylloxera, to make and repatriate wine for use in their own markets. This left a long-term mark on Rioja, establishing the Bordelaise habits of repeated and extended handling of wine in small barrels. This is fairly shallow (that is, relatively recent) history, however. Further, there is nothing to suggest Tempranillo’s tannins require the same polymerisation and taming as do those of Cabernet. There are many producers handling their Riojas both less and differently, and in the process arguably making more naturally shaped and scented wines, reliant less on winemaker artifice and artefact, and more on site, fruit character and quality. Such Riojas remain un-nameable.

If I age my wine in concrete, or in oak of larger format than 225 litres, it is only allowed to be sold as Rioja Generico. If my wines are un-racked, un-handled, and oak-aged for just the right time, rather than according to abstract recipe targets (24 months gets me Crianza $, 36 gets me Reserva $$, 60 months and I’m swimming in a deep pool of Gran Reserva $$$) … I only have Rioja Generico to identify by. If my wines are a careful, grown-not-made nurturing of countryside-to-bottle with minimal intervention, Rioja has no language for me.

The vineyard as time machine? (a place where the past becomes the future … )

I have spent many years waiting for a very special wine to be released. Telmo and Pablo from the Compania de Vinos Telmo Rodriguez have just released ‘Las Beatas’ 2011. This is a single vineyard wine from the village of Briñas, a very cold spot under the Montes Obarenes between Haro and Labastida. The vineyard is an amazing heritage site- a natural field blend of eight grape varieties and many variants thereof (red and white varieties, Tempranillo, lots of Garnacha and others, some clones probably only existing now in this vineyard), abandoned through much of the 20th century. Telmo and Pablo have spent many years restoring Las Beatas with its own genetic heritage material without realising any wine until releasing the 500 bottles of 2011.

Telmo and Pablo see Las Beatas as an exercise in cultural heritage, preserving the memory of Rioja from long ago, before the industrial Riojas of the 20th century. Here they are attempting a single vineyard Grand Gru, an emotional place of great significance, seeking to “reproduce from memory, a museum of what was the real Rioja” before the advent of Rioja Reservas, “where the process is more important than the origin”. Extraordinarily complex, gently fruited, gently earthy, gently rounded and seemingly free of winemaking, it’s guileful, wonderful wine and history lovingly restored. The only term available to describe it is as DOCa Rioja. It is indeed a very delicious $400 bottle of Rioja Generico … the legacy of a GI which recognises process and has nothing to say of place.

A soil-based distinction at the very least is required in La Rioja – one which acknowledges that only a very small proportion of the appellation’s 60,000-odd hectares features the cold, hilly limestone-clay soil profile preferable for high quality red wine production. Outside this soil profile, which demarcates a coherent region I am calling ‘Rioja Superior’, much very ordinary, pragmatic ‘supermarket’ wine is made. This is not to argue that no good or even great wine is possible in the richer, warmer alluvial soils, but we must admit that very little good-to-great wine comes from the greater part of the region. Curiously, the best wine outside Rioja Superior is actually from an outlier patch of soil very much like that of the core. Under Mount Yerga, near the village of Alfaro, deep in the south-east of Rioja Baja, are some very cold calcareous hills which produce outstanding Garnachas, deserving of a place in the roll-call of Rioja’s finest. These are among Rioja’s highest sites and constitute an outlier village appellation opportunity (Alfaro – Montes de Yerga) to add to the named villages of Rioja Superior, in the same manner that Fixin is a village of the Côte D’Or.

Towards a revised framework for regulating and describing ‘Rioja’

Much work needs to be done to organise and promote a quality-oriented taxonomy of the wines of Rioja. Here are some basic ideas on the matter:

· A new appellation, DOCa Rioja Superior, would indicate wines grown entirely within the specific terroir of the cold and low nutrient limestone-clay hills of the north shore. This zone is a soil-based sub-section of the land currently appellated as Rioja Alta/Rioja Alavesa.

· DOCa Rioja wine as a base appellation would refer to wines which are: 1) grown on soils outside the Rioja Superior zone; or 2) to wines which blend the soils of the north and south banks of Rio Ebro. I have no issue with a third base classification, for wines which are entirely made from the fertile soils south of the River, and I would support ongoing use of the name Rioja Baja for this. So, our taxonomy could be: Rioja Superior, Rioja Baja and Rioja (for wines blending Superior and Baja), but I would be happy with the simpler model that wines are either Rioja Superior 100% or they are simply Rioja.

· DOCa Rioja Superior wines should be able to further distinguish a discrete village origin on the label, should fruit for a given wine come from entirely within a particular town or village municipality. So, for example, Telmo Rodriguez, who’s Lanzaga wine is from a hill adjacent to the village of Lanciego (or Lantziego in Basque), would be entitled to label this as Telmo Rodriguez ‘Lanzaga’ DOCa Rioja Superior – Viñedo en Lanciego. Likewise, in the hills above Alfaro in the south-eastern corner of Rioja, Alvaro Palacios would be entitled to label his family’s Propiedad wine as Palacios Remondo ‘Propiedad’ DOCa Rioja – Viñedo en Alfaro, Montes de Yerga (this would require the foothills of Yerga Mountain, part of the village of Alfaro to be recognised as an outlier component of Rioja Superior on the basis of soil type).

· At the village level, individual vineyard names would need to be recognised, but also ‘place names’ – Parajes (surveyed sections of towns, like lieu-dits). These already exist according to historical cadastral mapping, and such ‘places’ are already recognised in Priorat, where they are termed, in Catalan, Partidas. In the near future, when DO Bierzo re-describes itself geographically, the hierarchy of wines made at Descendientes de Jose Palacios by Ricardo and Alvaro Palacios will be labelled in order of specificity: DJP ‘Corullon’ Viñedo en Corullon (village wine), DJP ‘Moncerbal’ Vino de Paraje de Corullon (specific place within Corullon village) and DJP ‘La Faraona’ Vino de Finca de Corullon (specific vineyard within the municipality of Corullon). In fact, it’s not yet clear whether Bierzo will call them Parajes or the more local term – Suertes.

· I would recommend that Crianza, Reserva and Gran Reserva appellations continue to be legal. Much as I am un-fond of the many poor thin and oxidised wines made under these handles, not all are terrible. The first problem is simply that these factory references are the only available quality differentiator allowed in contemporary Rioja. As such, they serve to shore up the position and price of way too much over-priced and under-ambitious industrial wine from the big companies. In passing, one of the stupidest wine laws in existence is hidden in this model, which is that you can use new wood, old wood, French, Missouri or any other oak – and probably pine for that matter … but if you want to market your wine with an age-related predicate, a Gran Reserva for example, it must be aged in a 225 litre barrique! At the same time, some of the best and most exciting small producer, place-specific, ‘grower’ wines of Rioja are being made and aged in concrete, in 600 or 2000 litre wood and thus are only allowed to be called generic Riojas). The point is not so much to attack the Crianza-etcetera model, as to allow site-specific producers to use place as an indicator of character in a way commensurate to that afforded to industrial practice. Indeed, I would imagine a number of producers would wish to combine the two ideas and release wines labelled, for example, as Bodega Roda ‘Roda 1’, DOCa Rioja Superior – ‘Reserva’ Viñedo en Haro.

· I would not imagine any necessity to stipulate that Rioja Superior was the Tempranillo zone and that Rioja Generico or Baja was a Garnacha zone. Although Tempranillo is almost always better in the cold soils above the river, it is too restrictive to say that only Tempranillo from the Superior zone is acceptable as basic Rioja. For starters, this would mean that the 90% of the soils south of the river currently planted to Tempranillo (in the current swing of fashion) would be void as Rioja. Almost certainly, this would promote higher overall quality, but economically it’s perhaps a little strict? Besides, what of the ancient vineyards of the north which are historical field blends where Garnacha and other varieties are naturally mixed with the Tempranillo?

Currently everything gets in the way of a clear understanding of place and quality in Rioja, and it is a crying shame. It’s a beautiful place, capable of lots of good and some very great wine. The combination of a deficiency of permitted geographical expressions and an official preference for factory logics occludes the work of those seeking to be growers, rather than makers. And let’s not even get started on what it might mean to use terms such as Modern, Classical or Traditional Rioja … with Rioja in its current state, that’s trickier than Alice going down a Rabbit-hole!

The traditional Alta/Alava/Baja view of the principle regions of Rioja

END OF SCOTT’s ARTICLE

Maps of Rioja

Rioja and it’s three current subzones Alta, Alavesa and Baja achieve no meaningful distinction between vineyards and wines.

Baja translates to Low and is being replaced with Oriental given the negative quality conation of the word.

There is a growing push to better recognise quality terroir by define the:

- Quality soils in Rioja at a macro level, equivalent to Appellation Bourgogne in Burgundy;

- The individual villages or Pueblo of Rioja equivalent to a village in Burgundy like Gevrey-Chambertin or Chassagne-Montrachet; and

- The special places (like lieu dit in Burgundy) & individual vineyards within the villages.

Only time will tell how this unfolds. In the meantime we’ll be including information on all of the wines we list from Rioja.

The area is vast with over 60,000Ha of vines planted. As Scott Wasley puts it, it’s the equivalent of using South East Australia to classify the wines NSW, Victora, SA and Tasmania. In the flyover below at the 20sec mark you’ll see a high level geological map of general soil types, it’s clear they run perpendicular to the general sub-region orientation along a number of rivers, valleys and sub-plains. The fact that I’ve mentioned both the split in soil types, and, significant geological changes if enough for any vigneron worth their salt to call for a more detailed differentiation between key viticultural areas of Rioja. Politics, corruption and a bias toward bland mass-produced wines the adversaries of progress on mapping the region. Without more appropriate classification of vineyards we have to rely on the reputation of quality producer and their track record in the glass. Perhaps not a bad thing for an individual wine. Not great for the reputation of a region as a whole.

Although not an official classification the map below would be a start to delineating between different areas of Rioja based on the Valleys within it. You can clearly see the rivers running through each of the valleys.

General in nature the soil map below offers some guidance on the geology of Rioja.

You must be logged in to post a comment.