Product information

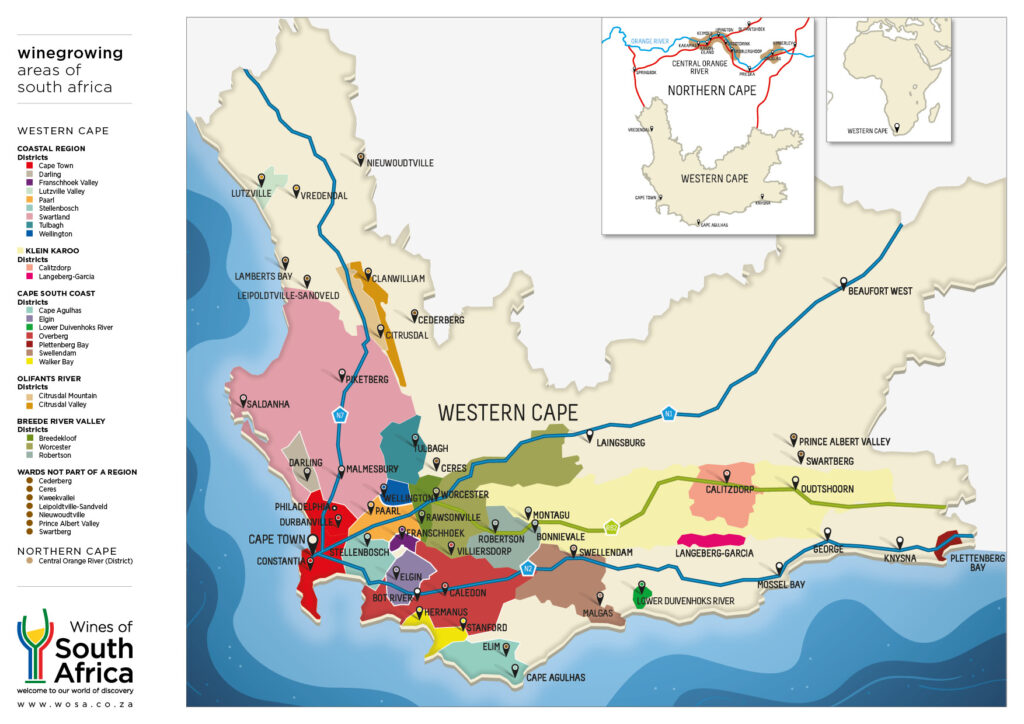

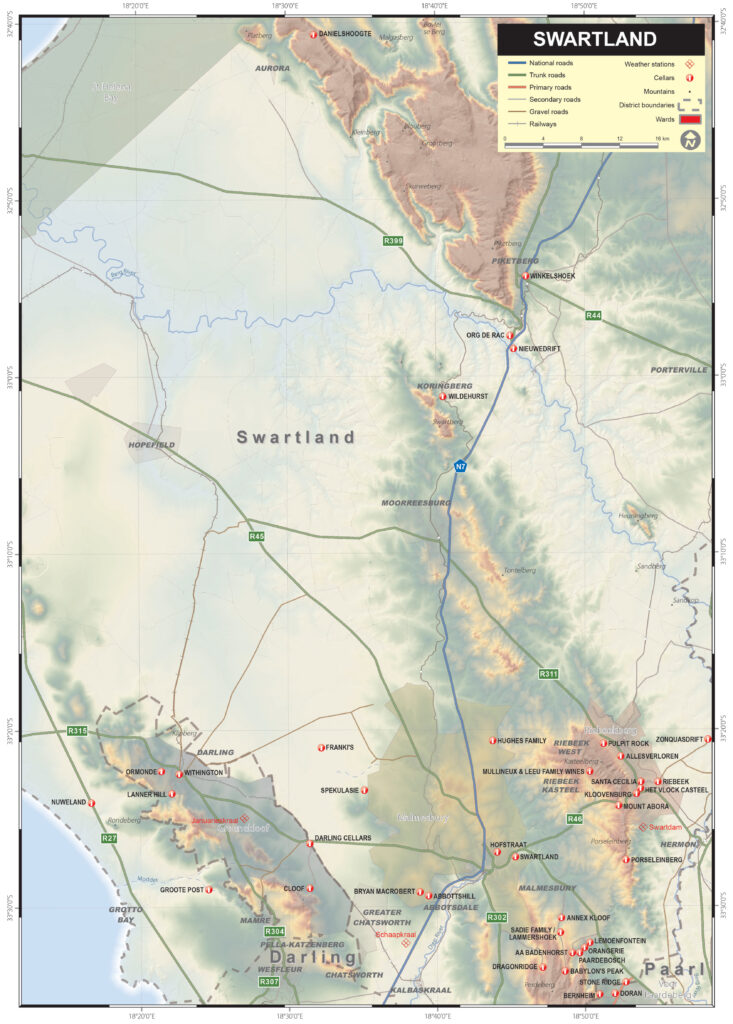

Sadie Family Swartland Treinspoor 2023

$183

Description

“The 2023 Treinspoor is pure Tinta Barocca planted on sandstone and granite/quartz. Dark berry fruit and hints of Earl Grey unfold on the nose that’s maybe just a bit Nebbiolo-like in style and very expressive. Brisk and bright, the palate is medium-bodied with slightly chalky tannins. It’s a little Barolo-like toward the grippy finish, leaving veins of blue fruit on the aftertaste. Outstanding and characterful.”

Neal Martin, Vinous 95 Points

“Treinspoor is a pure Tinta Barocca from red clay soils close to Malmesbury. Eben Sadie reckons it’s the “most elegant” expression of the vineyard yet, but this is still a wine that’s built for the long haul, with classic damson, fig and cranberry flavours, chewy, stubble-chinned tannins, a ferrous, steak tartare undertone and enough acidity to drive and freshen the finish.”

Tim Atkin MW, South Africa Report 2024 95 Points

In stock

You must be logged in to post a comment.