Thankfully the story of Priorat is becoming a common story of the renaissance of an abandoned wine region. It goes like this, commercial realities force vineyards to be left to ruin as the local population moves to nearby cities. Decades if not centuries later a few passionate indivivuals get together with the plan to make quality wine, harnessing old vineyards and planting new ones with grape varieties from around the world. They play with the new varieties, technology and lots of oak. Then an epiphany comes and they go back to the old ways of their great, great, grandparents. They use the local varieties, look to express fruit, offer restraint and balance their use of oak.

What do they taste like?

The best of Priorat have evolved into sophisticated creatures full of personality. The incredible high elevation vineyards, planted on slate, many over 100 years ago, yield little fruit, what little they do yield is exceptional.

Natural acidity sees many running with acid levels similar to crisp white wines. The way the tannins, fruit, alcohol and acid complex and balance together gives us superb mouthfeel.

The Reds

Although several French varieties are prominent in the region, sticking to the native varieties, on the red front have the option here to try wines made of the two hero varieties Garnatxa (Grenache) and Carinyena (Carignan) both indiviually and as a blends, some times with a small percentage of white grapes. Like so many varieties around the world, the clones here are unique.

Intoxicating perfumes, vibrant, red fruits, sometimes red apple and pomegranate come to the fore in the Garnatxa, earthy, dark savoury traits in the Carinyena. That overlay of soot, licorice and more often present.

The Whites

And, that’s just the reds. The whites made from Garnatxa Blanca, Pedro Ximénez, Macabeu, Moscatel are invigorating. Fresh, zippy, texutrual, again with insane perfumes.

Two words on the capsule of Àlvaro Palcios’ wines sum it up beautifully:

‘Personalata Única’

Deep Dive

Watch the video and read the booklet republished from the works of Scott Wasley and you will see this story told in the context of Priorat.

Check out all the Wines from Priorat!

The following has been republished with permission from a booklet by Scott Wasley of The Spanish Acquisition. Scott imports a great many delicious Spanish beverages and is a font of knowledge! The content is unchanged with the exception of some of the media.

DOQ Priorat and DO Montsant

by Scott Wasley, The Spanish Acquisition

CONTENTS

Intro

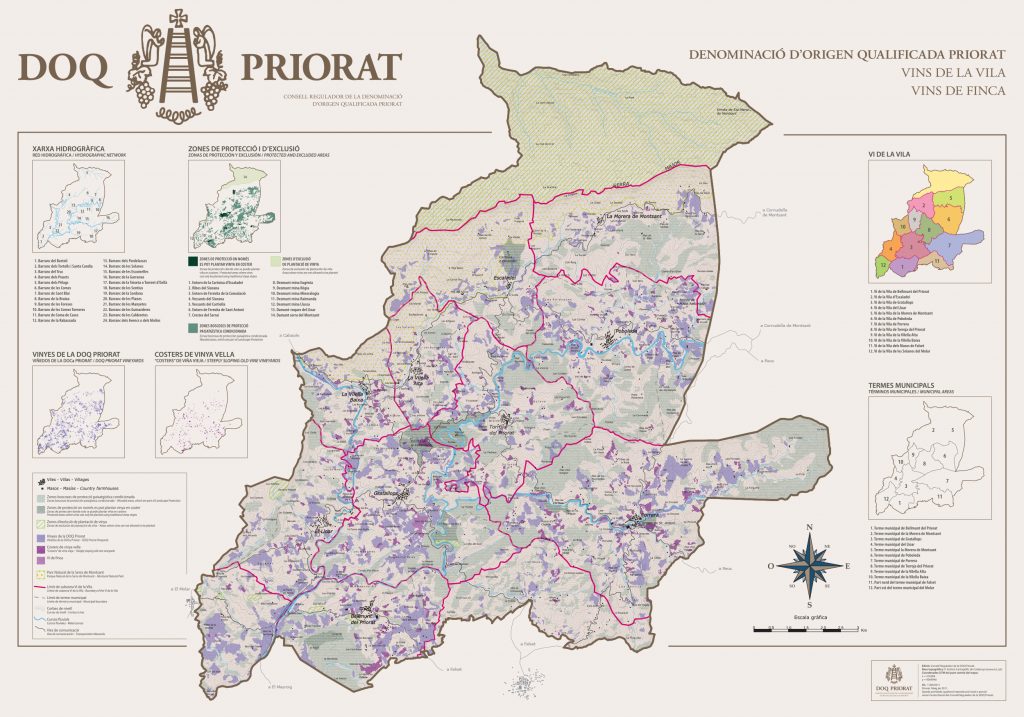

Map

Basic wine characteristics: wines that smells of suits?

A wine history of Priorat in numbers: rise, fall, rise

Then came the Priorat 5

Priorat into the 21st century … the unlikely progressiveness of the Consell Regulador

More on geography, climate, soils

Grape varieties of Priorat and Montsant

Meanwhile, in Montsant … (enter the post-modern co-op)

End Notes

INTRO☝︎ Index

A place with two place names, containing two appellations

SERRA MONTSANT – the name of the mountain range circumscribing the region.

PRIORAT COMARCA – the council name of the region – its socio-political identity. The Comarca itself is named after the Priory at the village of Scala Dei, on land gifted to Carthusian monks by King Fernando 1st in the 12th century.

DOQ PRIORAT – a wine appellation in the centre of the Montsant range’s valley, defined by schist soils.[1]

DO MONTSANT – a wine appellation within the Montsant range encircling DOQ Priorat, based on limestone soils.

(FRIED) EGG THEORY☝︎ Index

The two appellations are delineated by soil type.

Pull out your drone and imagine the valley floor lying flat below you (which it absolutely is not), resembling a fried egg. The perimeter (the white) is limestone soils which are defined DO Montsant. The coloured interior (the yolk) is a mix of blue and brown slate, and these soils, locally known as llicorella, are DOQ Priorat.

Driving north out of the southern ‘capital’ Falset, you can sense the change in soil, the delineation of appellations in a visceral, immediate manner. As you swing left around a bend 3 or 4km out of town, towards Gratallops, you cross from limestone into slate, and it’s like someone just pulled the blind down in a lounge room on a sunny day.

YOU ARE NOW ENTERING PRIORAT …☝︎ Index

90 minutes south of Barcelona, in the province of Tarragona and just 20 minutes in from the coast, Priorat and Montsant are wine regions within the majestic Montsant mountain range.[2] The normal entry to the region (coming from Barcelona) has you arriving in the main town of the region, Falset, in the southern third of the area and on the cusp of the Priorat and Montsant wine appellations. On approach, driving up the back of the Montsant range, rising up out of the flats of Tarragona, the heart quickens. Breaching the encircling mountains and looking over the hilly valleys within feels as if discovering an ancient, hidden land for the first time. And so it is …

Within, the Montsant escarpment dominates the landscape. It’s hilly everywhere, with very little valley floor, just tight river valleys below ancient hillside villages. The villages (pueblos, in Castellano, vilas, in Catalan) are linked by tiny local roads winding through the internal ranges. Vistas appear and close off in constant flicker. Everywhere, the limestone Montsant range looms, remote and watchful. The northern parts are the hilliest, highest and greenest, and lavishly forested despite the general dryness of the region. In the south-western quadrant, the hills unwind, rolling out to the Ebro River delta and the Mediterranean. The vines cling precariously to the steep, rocky hillslopes.

BASIC WINE CHARACTERISTICS☝︎ Index

Wines that smell of suits?

There is a smoky-but-fresh mineral soil character in DOQ Priorat wines which is unique – a dominant terroir smell characteristic enough to unify varieties as disparate as Garnatxa and Cabernet in a meaningful sense as Priorats. On my first visit to Alvaro Palacios, I asked if they had a word for this distinctive soil smell, and was told:

“yes, it’s SUIT!”

“Suit?”

“Yes, you know – like the black dust in a chimney?”

… “Aaaah, soot!”

Indeed, great Priorats do have a ‘sooty’ ashy mineral smell – a dark, polished and fine mineral earthiness with fantastic clean, reaching steely freshness. The minerality of Priorat llicorella often has a subtle truffled-honey aspect, along with licorice, and other earthen tells of dry stone, sand and clay. Although ripe berry smells of red and black forest fruits are the obvious story of Priorat wines, in all the best expressions, these fruits are subsumed in, and moderated by fresh earthen minerality.

Hand in hand with the smell of the earth in Priorat wines are balsamic characters. Essential oils (the terroir from above) imbue wines with the landscape’s fresh pungency: aniseed, mint, thyme, rosemary and much more abound.

This is warm country, which naturally makes full-bodied wines, mostly dry reds. There’s a bit of – increasingly good – pink and white too, and some remnant old sweet/rancio styles. In the past, Priorats were often hot, heavy wines, extracted and oaked without subtlety. Such wines remain easy to find … however, the regional offer increasingly features fresh, vital, lively and highly drinkable wines. The best wines of Priorat are nimble, with fruit concentration a secondary factor behind (within) countryside smells of herbs, balsams and the fresh mineral jag of the llicorella.

The history of wine here is complex, even when talking about the region’s main (red) grape variety.

Yes, Garnatxa is the standout local cultivar[3], but until recently it accounted for very little of the region’s crush. Carinyena[4], a French grape, accounted for most of wine production during the tough times after the Civil War.

An outsider? A bulk grape?

Yes and yes, and we are right to celebrate the return to prominence of the native Garnatxa.

At the same time, with increasing vine age and the luxury of care and investment in the variety, many producers are experiencing, and promoting an upswell in the esteem afforded to Carinyena.

Cue the Soviet propaganda card:

“Glorious llicorella elevates a French workhorse into something it has never been!”

Priorat is midstream of an ongoing cycle of regeneration, and a new wave of village-specific producers are demonstrating increasing confidence in and commitment to the nuances of the region’s identity. Good news.

But we need to understand what was lost, in order to appreciate the gains being made in the current era …

A WINE HISTORY OF PRIORAT IN NUMBERS: RISE, FALL, RISE …☝︎ Index

10,000 hectarios

In the late 19th century, DOQ Priorat had vast historical plantings, perhaps more than 10,000 hectares under vine. Locally-adapted Garnatxa cultivars dominated, and were planted and pruned according to knowledge acquired and refined over centuries. All viticulture was organic, and the best grapes grew on the poorest hillslopes. Then came phylloxera, in 1893, and afterwards the various blights of the 20th century.

Re-planting in the early 20th century on American rootstocks saw a quick recovery from the devastation of phylloxera. By 1930 the historical genetic material and associated planting patterns had been re-established – the patrimony of the land, the ‘long history’ of Vitis Vinifera adapting in this place, was being restored. At first, even the disaster of the Civil War seemed not to interrupt recovery too much. The last great vineyard of the region, ‘L’Ermita’, was planted in 1939, by which time perhaps half of Priorat’s historical vine lands had been re-established.

750 hectarios

But recovery stopped dead then: instead of recovery came ‘the abandonement’.

During the half-century of fascist rule after the Civil War, a number of ills befell wine regions such as Priorat and Montsant. Economic pressures favoured volume over quality: plantings tended toward the more fertile soils and towards higher cropping varieties – toward the reliable big-colour, big-yield Carinyena rather than the more fickle Garnatxa. Socio-economic pressures also devalued country life, and youth left to seek work in the army, the mines and the cities. De-population and economic depression saw plantings diminish in quantity along with lower quality. Generational renewal ceased; the population aged. Through the second half of the 20th century, most of the land under vine returned to the forest as capital fled to the cities.[5] Old costers vineyards were being abandoned right into the ‘90s. Priorat’s area under vine declined to a mere 750 hectares by 1989, of which 75% was Carinyena. Even when the fascist regime ended (in 1975, or 1978, or 1982 depending on the marker you choose), social and economic recovery took time. Particularly in the countryside … Priorat was “a desert of grape vines” (Alvaro Palacios).

2,000+ hectarios y contando …

Since 1989, a rebirth has taken place.

Now there are 2,100 hectares of DOQ Priorat, and about 40% is Garnatxa, with 600 growers and 100 producers.[6]

THEN CAME THE PRIORAT FIVE☝︎ Index

One of the most important ‘moments’ in Spanish wine history came in 1989, when a group of five converged in Priorat with the intention of preserving and re-interpreting the vanishing old vines of Priorat. Alvaro Palacios ventured into Priorat with Rene Barbier, who worked at the time for Alvaro’s father Jose at Palacios Remondo in Rioja (Rene had been checking out Priorat for a decade by this time). Rene and Alvaro led a group which also including Daphne Glorian, Josep Lluis Perez and Carles Pastrana. Sourcing neglected old vines from the hilltops of Priorat, these five made a single garage wine together in both 1989 and 1990 and bottled a fifth each under their own labels (the wine was bottled without DO as ‘Costers del Siurana’):

· Alvaro’s eponymous label, ‘Alvaro Palacios’ (originally ‘Clos Dofi’)

· Rene Barbier’s ‘Clos Mogador’

· Jose Luis Perez’s ‘Clos Martinet’

· Daphne Glorian’s ‘Clos Erasmus’

· and Carles Pastrana’s ‘Clos de L’Obac’ (nowadays, ‘Costers del Siurana’).

Below are the Priorat Gang of 5 without Carles Pastrana.

Even today, the 1989 has all the tells of Priorat: spicy red fruit, fennel, faded roses and countryside smells of medicinal herbs, bosky woods, cold dark rocks, mineral, licorice, soot, brick dust and balsam.

Much of import spun out from this moment. Much of it good, although for a time it seemed the initial boon might quickly become a blight. ‘Los Closos’ first releases were embraced wholeheartedly by wine blogger Robert Parker Junior. Big Parker Points meant big $$ in the US and there was now a ‘Priorat Boom’. Going from ultra-low-value co-op plonk to US-hyper-bucks in about 5 minutes, the value of Priorat fruit was renewed instantly. Founding the DOQ in 1999 effectively wiped out the grey market for DO Catalunya wines made from Priorat (and Montsant) fruit, which was now bound by a rule that 95% of production must be grow and bottled in the DO.

It also let to a crass rush to mine Parker points from the slate.

“by the late 1990s, the football stars, the singers, Gerard Depardieu – all the people nobody needs – were in Priorat because it was hip and they could show off that they could afford to buy a winery in Priorat …”[7]

Predictably, this lead to an instant ‘investment’ wave and every man and his banker took to Priorat like a new el Dorado – only here one mined for Parker Points.

Damn, man, they were virtually lying on the ground!

The minute the low-crop old-vine mountain Garnatxa was ‘discovered’ in Priorat (even ‘though virtually none such actually existed), a fool’s gold rush ensued. Large companies came and bought up tracts of land, cutting new terraces and planting broad-acres on trellis … and for a decade it seemed that precisely in the moment that Priorat was found, it would also be lost. The influx of big-Capital broadacre producers was shortlived, however, and Priorat has largely settled into the hand-crafted small-maker mode which seems to best fit the difficult sites and shy-yielding vines which suit these poor soils … “there are no hectolitres in Priorat!”[8]

PRIORAT INTO THE 21st CENTURY☝︎ Index

… the unlikely progressiveness of the Consell Regulador

Spain’s DOs are corrupt.

The Consejos Reguladores of wine regions like Ribera del Duero, Rioja, Rias Baixas and more are typical of a very Spanish conjunction of overweening bureaucracy and flagrant corruption, glued together by the cheap glitz of Big Company Money (Clive Palmer would do well in a land such as this). In Spanish authorities, one can find the antithesis of progress, reason and dress sense.

However, DOQ Priorat is blessed with a relatively progressive official body.

Priorat became an appellation in 1954, the year after Rioja, and was confirmed at the more rigorous classification, DOQ in 2000. The Consell Regulador (offices in Torroja) stood up for a fight in 2007 and bucked Spain’s dire anti-GI laws.[9] In 2007, they brought in a major reform aimed specifically at recognising sub-regionality on a village-by-village basis. There are now 12 sub-regional ‘Vins de la Villa’ appellations, taken from the official 9 Villages of Priorat, plus Scala Dei and 2 Montsant villages whose municipalities contain discrete parcels of schist soils designated as Priorat terroir.

So, if you have vineyards within a certain village municipality within DOQ Priorat, say Gratallops, and your wine is entirely grown, made and bottled within the municipal bounds of this village, you may release your wine as DOQ Priorat – Vi de la Vila Gratallops. Furthermore, if your wine is from a single vineyard entirely within a village boundary, you may release it as a Vi de Finca – a specific vineyard within the Vila. In between Vi de Vila and Vi de Finca there is also an intermediate toponymic appellation, Vi de Partida (wines of place, like the lieus-dits of France; also spelt Paratje, Paratge).

Priorats Vis de Vilas:

· In the North are the Vis de la Vila d’Escaladei, la Morera de Montsant and Poboleda.

· The Vis de la Vila of central Priorat are: Torroja del Priorat, la Vilella Alta, la Vilella Baixa and Porerra.

· In the south, Gratallops, el Lloar, Bellmunt de Priorat, Masos de Falset and les Solanes del Molar.[10]

Other regulative stipulations:

Vi de Costers is a label permitted to old vine Garnatxa vineyards: they must be uncut (not terrassed), be on pure llicorella, and are typically planted across the slope, at planting spacing of 150×125, with about 5000 plants/ha.

Vins Vells (in castellano, Viñas Viejas, are currently stipulated to have been planted in 1960 or older.

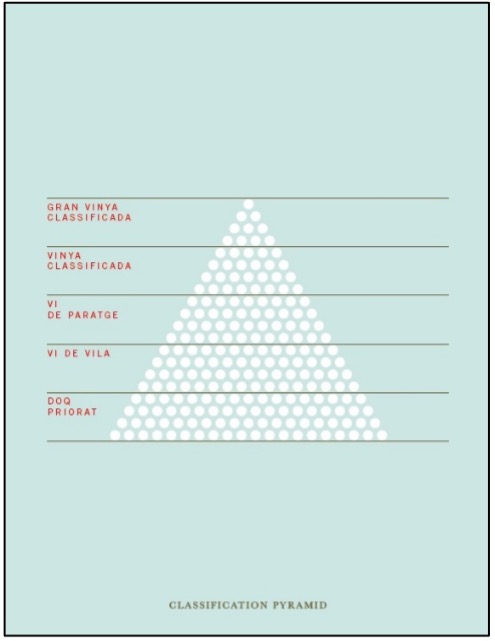

The classifications in Draft, 2016

An addition by WINE DECODED

VINO REGIONAL (regional wine)

– Wines from grapes from any of the villages within the appellation

– Maximum yields allowed: 6,500 kilos per hectare

VI DE VILA (village wine)

– Wines from vineyards from only one village

– Maximum yields allowed: 3,700 kilos per hectare

– Still discussing if minimum age of vines should be a requirement

VI DE PARATGE

(Tricky discussion about the English translation of the name: a paraje (or paratge in Catalan) is a zone larger than a single vineyard; there’s no equivalent in the Burgundian hierarchy and it means literally ‘landscape,’ but I was proposing a free translation like ‘quarter.’ In any case… ideas are welcomed!)

– Wines from a specific quarter/zone within a village

– Maximum yields allowed: 2,800-3,000 kilos per hectare (still under discussion)

– Minimum age of vines to be defined

– This would be an intermediate stage before achieving the following category of…

VI DE VINYA CLASIFICADA (wine from classified vineyard)

– Wine from one or a number of vineyards within a zone/quarter (paraje) of one village

– Maximum yields allowed: 2,800-3,000 kilos per hectare (still under discussion)

– Minimum age of vines to be defined

– Five years of traceability in the vineyard and ten years of international recognition in terms of market and local and international opinion leaders

– Other things that are still open is if they are going to limit the maximum size of the vineyard and if organic farming should be mandatory

GRAN VI DE VINYA CLASIFICADA (great wine from classified vineyard)

– Wine produced with grapes from a single vineyard

– Maximum yields allowed: 1,800 kilos per hectare

– Minimum age of the vines: 35-40 years (still under discussion)

– Traditional viticulture on slopes (coster) in shaded areas (umbría) and organic farming (an open point)

– Five years of traceability in the vineyard and ten years of international recognition in terms of market and local and international opinion leaders

MORE ON GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE AND SOIL☝︎ Index

Remote, dry, craggy and extremely beautiful, the Montsant range frames 500 square kilometres of mostly hill country covered in red pines, olive, almond, hazelnut and encina (Holm Oak), all growing in soils 300-400 million years old. The region is cut into three valleys by Rios Siurana, Cortiela and Montsant. The three rivers converge at el Lloar and flow southwest to join Rio Ebro on it’s way from la Rioja and out to the Mediterranean, just 20 kilometres away. Afternoon heat is often relieved by this coastal proximity, as Garbinada breezes freshen from the south-west (and from the north, the serré).

The Montsant range is a warm, dry, hilly region perfectly suited to the local red variety, Garnatxa and its running mate, Carinyena. The western part is sunnier, drier and more open, better suited to Garnatxa, and Gratallops is its main wine town. The eastern side around Porrera is higher altitude (up to 750 metres), and fresher with tighter valleys, and is home to the finest Carinyena. Rainfall averages around 500mm, wetter in the north than the south. Being very dry, mildew and botrytis are not problematic and about 50% of plantings are organic, although some choose to use chemicals to combat viticultural issues such as oidium and the Lobesia moth.

The region has several soil profiles:

· Llicorella (brown or blue schist-slate soils which yield rich and very mineral wines)

· Calissa (limestone, giving fresh and floral wines from very deep-rooted vines)

· Argila (clay, producing edgy and wild wines as vines battle in the dense soil)

· and Panal/Calcare (sand soils – washed out alluvium from the limestone, called Calcares if pebbly – these give fruity, easy wines marked by chalk).

Of these, the schist and limestone are the most important, and determine the identity of the two DOs – Priorat and Montsant. DOQ Priorat is almost pure schist (slate) soils, locally known as Llicorella, of which there are several blue and brown variants. DO Montsant’s soils are about 70% limestone matching the heart-rock of Serra Montsant. The rim of the region is DO Montsant, which wraps all the way around the schist soils of DOQ Priorat in the heart. Much of the land given to grape growing is very steep, and the archetypal vineyards are grown ‘en Costers’: bush vines on very steep slopes.

High elevation old vine planted on Licorella at Mas Doix

GRAPE VARIETIES OF PRIORAT and MONTSANT☝︎ Index

“the music, the poetry, finesse and vibrancy is in the Garnatxa”

Alvaro Palacios

Debate persists about whether Garnatxa is transplanted Grenache introduced here by French monks, or whether it is entirely of local origin, and was exported to the French. After a thousand years of local evolution, the Garnatxa of the Montsant range is entirely adapted to the locale, and is different to Grenache elsewhere. The local Garnatxa Negre has a variant called Garnatxa Peluda, or hairy Garnatxa, which is in fact derived from French Grenache. However, this strain was introduced a couple of hundred years ago and it too is highly naturalised. The other main local grape is Carinyena (elsewhere known as Carignan, among other names). Cabernet and other French red grapes have become common in recent times. There is also a small white grape presence, mainly Garnatxa Blanca.

Permitted and preferred grapes

RECOMMENDED

Garnatxa, Carinyena, Garnatxa Blanca, Pedro Ximénez, Macabeu, Moscatel

AUTHORISED

Cabernet, Syrah, Merlot, Pinot, Viognier, Chenin Blanc

TOLERATED (JUST)

Monastrell, Chardonnay, Picpoul

In 2013, the harvest from 2000 hectares under vine in Priorat was 54 million kg, 95% of which was red. Of this, 40% was Garnatxa (Negra y Pelluda), 21% Carinyena, 14% Cabernet, 11% Syrah, 7% Merlot, 3% Garnatxa Blanca and 1% Macabeu with traces of Cabernet Franc, Tempranillo, Pedro Ximenez, Xarel.lo, Viognier, various Moscatels, Chenin Blanc and Picpoul Blanc.

Garnatxa and Carinyena (formerly Cariñena, also Samsó, Caranyena … some even call it Carignan)

Garnatxa (in catalan, Garnacha in castellano) is very widely grown throughout Spain, just like Grenache in France. Garnatxa is the parent grape, but there has been plenty of genetic to-and-fro. The general name for the grape in Spain is Garnacha Negre. It buds early, ripens latish and has moderate acid, and higher tannin than Grenache.

There is a variant common in Priorat, Garnacha Peluda, or Hairy Grenache, with one reflective and one absorptive side of the leaf, and this variety has a shorter vegetative cycle. The fur is an anti-heat adaptation. Its wines are lower alcohol but can be prone to oxidisation.

Garnatxa/Grenache is often used to make pleasantly fruity, off-dry pink wines – sometimes at the high end of the alcohol spectrum. Being low in phenolic material (usually), it is well-suited to producing café-quaffer light reds. As elsewhere, low crop levels, dry growing and old vines can produce rather more affecting fruit, and there are a significant number of Spanish Garnach/txas which produce rich, dry, earthy wines with concentration, structure and length enough to handle oak treatment and succeed as premium dry red table wines. But nowhere does it achieve the finesse and beauty attained by Priorat’s finest Garnatxas.

Quality in Garnatxa is closely tied to yield. On trellises it yields too much, but careful growing en vaso or en parra (bush vines on the ground or trained on a pole) controls yields for much higher quality. Priorat Garnatxa has high natural acidity, particularly tartaric, and a refreshing juice profile, with orange, blood orange and ruby grapefruit flashes among the common rosehip, plum and red berry characteristics. The short vegetative cycle of Garnatxa is well suited here, with rains common in mid-September.

Since phylloxera, problems with the economy of Garnatxa saw it lose ground to Carinyena, particularly in the poverty of the post-‘40s abandonment era. Most view Garnatxa, in the guise of it’s derivate, Grenache, as a hardy country plugger … under adversity, so the story goes (and the hotter, windier the better), Grenache will give you a reliable yield from grapes as big as your head, which grow easily and give you plentiful, cheap, gluggable rustic plonk. If only!… Priorat Garnatxa is a fickle yielder anyway, with small bunches of small, skinsy berries, and yield dreadfully in the stony aridity of Priorat. Worse, on American roots it’s especially difficult to grow – it sets small, uneven bunches and when the yield gets to the bodega, it’s very difficult to ferment[11]. Ironically, ‘grenache’ was too mean-yielding and expensive to grow during the hard times from 1940 and the French workhorse, Carignan was recruited to provide reliable, economical yields.

Carinyena (in catalan), the Carignan of Southern France, was introduced to Priorat in the 18th century. It was spelt Cariñena (in castellano) until recently. You will also see it referred to as Carignan, or an empordan linguistic variant, Caranyena, and it’s known as Mazuelo in la Rioja. In the early 2000s there was after outcry from nearby DO Cariñena, which arced up at ‘its’ name being used for a grape variety grown elsewhere (ironically, DO Cariñena produces run-of-the-mill Garnacha). The bureaucracy installed Samsó as the ‘official’ name for the grape in the early 2000s. There are approximately zero producers in Priorat who identify with Samsó as this grape’s name, although many dutifully labelled their wines thus. This silly rule was revoked in 2018, and producers are able to revert to Carinyena. You’ll see all of these names, and possibly a true local variant, Crusilló in use. This is a very Spanish (and/or Catalan) normalcy. For simplicity’s sake, we will stick with Carinyena no matter what’s on a given label.

Either way, as a blender it adds structure, colour and acidity, and it yields well in Priorat. Much was planted during the abandonment years. With Priorat’s economic recovery after the 1990s, those who dry grown and low yield have found that old vine Carinyena can make utterly remarkable (dark, vegetal, leathery) varietal wines! Since phylloxera, Carinyena has virtually displaced Monastrell from Priorat wines – once important, Monastrell is nowadays barely tolerated by the Consell Regulador and never appears on labels.

MEANWHILE, IN MONTSANT … (ENTER THE POST-MODERN CO-OP)☝︎ Index

Meanwhile, literally across the road … In the southern part of the range, near the main town of the region, Falset, one crosses from slate to limestone soils and from DOQ Priorat to DO Montsant. While instant fortune came to Priorat after 1989, the poor farmers of Montsant were doing it tougher than their suddenly famous neighbours.

In 1933, five families in Capçanes village joined together to found a co-op and make wines from the vineyards being re-established after phylloxera. However, this development was almost immediately followed by the Civil War, during which time political divisions were felt within the village, even within families. Forgiveness and healing started after Franco’s death in 1975 and the restoration of democracy in 1978. On top of this rift, the devaluation of grape/wine prices and rural de-population were multiple hits during the mid-20th century, on top of the ills of war. The almost terminal descent in the fortune of the Capçanes co-op tells the general tale of DO Montsant perfectly.

It even has a happy ending …

By the 1980s and Spain’s ascension to the EU, Capçanes and its co-op were in dire trouble. Increasingly, city wine merchants bought in bulk and cashed in at the coast. By 1980, the region was only producing bulk wines. By the mid-90s, they could only sell grapes in bulk – no longer even having the relative dignity of being able to turn their grapes into wine (albeit to be sold under another’s name). The big company producers from DO Penedes and DO Catalunya bought Montsant and gained colour, extract, power and character for very little money. By the early 1990s, the biggest of these companies, Torres, was buying up all the land they could, particularly in Priorat, while land values remained relatively low yet wine prices were exploding. There was a very real fear for the growers of Capçanes that soon they would not even be able to sell grapes in bulk. Economic extinction loomed in Montsant while boom-time erupted in Priorat.

And then, something great happened! A Rabbi and a German helped the Capçanes Catalans save themselves. German winemaker Jurgen Wagner was working in the region as a wine-buyer for US importer Eric Solomon and saw the potential of the old vines of Capçanes, but it took a crazy twist to achieve the needed change. This came in the form of the Rabbi of Barcelona. Said Rabbi was looking to source a high quality Kosher wine for wealthy Barcelonan Jews, and the old vines of Capçanes were just the thing. Jurgen, along with the co-op’s then winemaker Angel Teixido, persuaded the 85 growers in the co-op to take a risk and provide their best, low-crop old-vine fruit to the Rabbi. In 1995 the first ‘lo mebushal’ Kosher wine was made by the Rabbi (in accordance with Jewish law, the Rabbi was the only one allowed to handle the wine). In 1996, the second vintage of Peraj Ha’abib somehow found its way into Parker’s hands, and it was rated just behind L’Ermita and Pingus as one of Spain’s highest pointed wines!

Thus, in 1996 the Capçanes co-op stopped selling its top fruit cheaply, instead value-adding it in their Kosher wine, realising their holdings’ full value for the first time. Torres responded by cancelling their orders for bulk grapes entirely. Capçanes were, officially, screwed.

Or were they? With no real option, they plunged into the deep end … a vote was taken and all but two of the growers elected to follow the urging of Jurgen and Angel. Capçanes become a ‘post-modern co-op’ making export quality wine bottled under the brand ‘Celler Capçanes’. These wines were to be viticulturally-driven, based on rigorous yield management and fruit selection from marvellous dry-grown old bush-vines. Make less but better wine and make more money (while controlling your own destiny), was the plan. A second, equally daring risk soon followed, with all 82 growers (by now, this number included Jurgen Wagner and Angel Teixido) co-signing to a capital-raising bank loan necessary to build a clean, modern winemaking cellar. This was an extraordinary risk on the part of extremely poor peasant farmers – a desperate leap of faith, which has paid off wonderfully. Nowadays, Capçanes produces several tiers of wine. There is decent quality cheap bag-in-box wines, there’s quite decent co-op plonk you can buy at the cellar door and take home in whatever vessel you bring to fill, and there are about 250,000 bottles of high quality export ‘estate’ wine. How ironic, Jurgen says that “narrow-minded Catholic mountain farmers would invest in the Jewish community to save themselves from Torres!”

Montsant achieved independent DO status in 2000. Prior to 2000, Montsant wines were appellated as a part of the giant DO Tarragona and recognised as a sub-section, called Zona Falset (albeit there was very little Montsant wine bottled as such until the advent of Capçanes in its revolutionary guise from 1996). While DO Montsant still lives somewhat in the shadow of DOQ Priorat, it is much re-invigorated now – led by Celler Capçanes, but with many emergent independent grower-makers entering the scene. Montsant, like Priorat, is beginning to re-interpret and write its own history as it moves through the early part of the 21st century.

END NOTES☝︎ Index

[1] Note, instead of Denominació d’Origen Qualificada Priorat, elsewhere you may see references to DOCa (Denominación de Origen Calificada) Priorato, which is Castellano (Spanish), rather than Catalan. As most producers in the region label in Catalan, rather than Spanish, we use Catalan terms and spelling where possible: DOQ/DOCa; Garnatxa/Garnacha. ‘Priorat’ is a term derived from the French for priory … the central (wine) factor in the region’s history was the (evidently thirsty) Carthusian monk retreat established at Scala Dei during the 12th century.

[2] We use the term the Montsant range to unify the series of mountains encircling Priorat. In fact, the Montsant range itself is the northern boundary, with Serra LLaberia in the south. The south-western boundary opens to the delta of the Rio Ebro and ultimately the Mediterranean. There are 50,000 hectares, of which about 17,000 are delineated as DOQ Priorat. To a certain extent, when we talk about ‘Priorat’ generally, we are discussing the land encompassing both DOQ Priorat and DO Montsant. That said, most of the fact-and-figure stuff here does refer specifically to DOQ Priorat. Montsant specifics are presented here as a separate end story, see page 8.

[3] The local Garnatxas can have an electric-OJ citric jolt: when coupled with llicorella’s mineral freshness and line, wines in a fluent, even poetic, register can result.

[4]Carinyena (perhaps, Caranyena) is the Catalan spelling of Carignan (it’s French name). see further notes in Grape Varieties section further on.

[5]The first bottling of Priorat wine since 1878 took place in 1974! Most wine was sold as ‘vi de granel’ … byo container wine.

[6] Adjacent DO Montsant had 10,000 hectares at the time of phylloxera, 10% of which was farmed by 2,500 peasants in the village of Capçanes alone. After the cycle of devastation and recovery, Montsant now has 2,000 ha under vine, 190 of which are shared by the 75 growers of the Capçanes co-op (the village now reduced to a population of 400). In 1990, DOQ Priorat and DO Montsant combined had 10 bottling wineries, by 2009 this had risen to 133. The Comarca del Priorat now totals 4,100 hectares of vines, down from a peak of 27,000, with an overall population of 10,000 where once lived 35,000.

[7](Jurgen Wagner, Celler Capcanes)

[8] A handy line given by one of Priorat’s current producers helps tie up the short version of the Priorat story. Big Company, industrial farming is ill-suited here. But to triumphantly hold out that Priorat is a natural home to the small, organic, artisan farmer and that its reality is wonderful old vine mountain Garnatxa is a little indulgent, however. For starters, there was actually very little old vine mountain Garnatxa left when ‘Alvaro and The Five’ descended. ‘L’Ermita’ is in fact the largest such chunk in existence, and it’s only just over a hectare in size.

[9]At the insistence of Big Capital, wanting to make generic wines and be famous for doing so, Village and Vineyard GI-specific naming of wines was outlawed in Spain during the 1980s … perversely, just as the post-Franco recovery kicked in!

[10] Note that the last two, Falset and el Molar are Montsant villages which have significant parcels of Priorat schist terroir in their municipality. So, most of the town land of Falset, for example is DO Montsant limestone and is thus DO Montsant Vila wine of Falset; however the northern reach of Falset’s municipal boundary is llicorella within DOQ Priorat and a variant Vila name, Masos del Falset applies for such land. The ancient Priory at Scala Dei, while not technically a village, is nevertheless afforded a Vi de la Vila appellation. The current Consell Regulador is Salustiá Alvarez, and his predecessor was local teaching academic Toni Alcover, who oversaw the re-introduction of true GI naming.

[11]A significant issue for the successful deployment of Garnatxa as leading lady of Priorat wines has been the difficulty of growing it on American rootstocks. Always a shy bearer, and difficult to flower, things got significantly worse on the most common rootstock – Rupestris du Lot. Nowadays a new hybrid, R-110 has significantly aided flowering and therefore the economy of growing Garnatxa in Priorat.

You must be logged in to post a comment.